What does the ACL do?

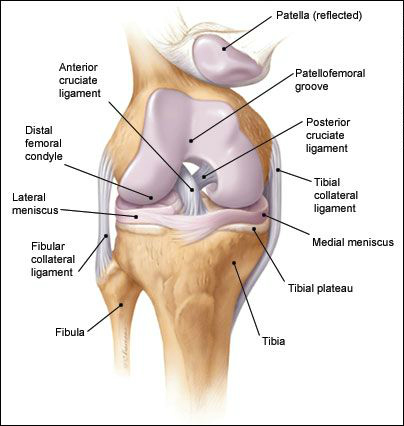

Within the knee joint, there are two main ligaments which act to stabilize motion – the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL and PCL). Anatomically, they “cross” each other in the center of the joint (Fig 1), hence the name ‘cruciate’. The primary function of the ACL is to prevent anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur (Fig 2). It also acts as a secondary restraint to tibial rotation. Both functions are accomplished through two separate parts, or bundles, which together form a ligament about as thick as your index finger. Of note, the ACL has its own distinct blood supply, which will be important for several reasons discussed later.

Fig 1

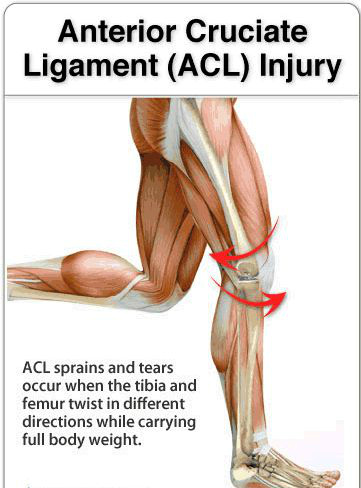

Fig 2

Why does the ACL tear?

Injury to the ACL typically occurs as the result of rapid deceleration and pivoting motion with the leg in hyperextension (Fig 3). What’s this mean? Picture yourself running full speed, then suddenly coming to a full stop and/or changing direction with your leg out straight (think about how many sports involve these movements – soccer, football, skiing – just to name a few). Of note, most ACL injuries are non-contact; in other words, it’s not caused someone running into you while doing all of the above (although it can certainly make things worse if it happens).

What are the symptoms of an ACL tear?

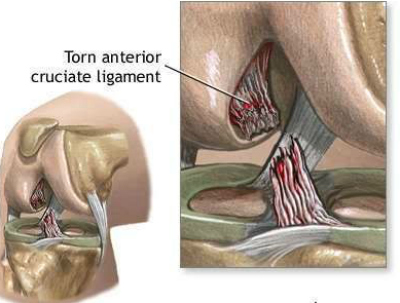

Patients will often report an audible ‘pop’ as the ligament tears, followed by deep pain and immediate swelling to the knee. The swelling is rapid due to the artery of the ACL, which also tears and bleeds into the knee joint (Fig 4). Long-term, patients with an ACL deficient knee report an inability to quickly start, stop, jump, or change direction without the knee “giving way”. Both sports and work-related activities are impaired, and because of the loss of stability, further damage to the knee can occur over time (eg arthritis).

How is an ACL tear diagnosed?

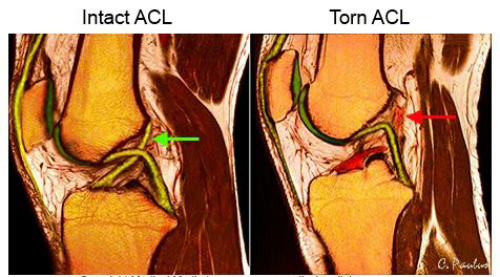

In most cases, the diagnosis of an ACL tear can be made by taking a careful history and knowing what to look for on physical exam. In addition to any obvious signs of trauma, there are specific maneuvers that an orthopedic or sports medicine trained physician can perform to test the integrity of the ACL. Confirmation of a tear is made by MRI, which is very accurate at imaging soft tissue (Fig 5). In addition to showing exactly where and how badly the ligament itself is torn, MRI can be particularly helpful in revealing any other injuries (eg meniscus or collateral ligament tears) that are often associated with an ACL tear.

What is the treatment for an ACL tear?

Treatment is highly individualized; bottom line: not all ACL tears require surgery. Nonoperative treatment is perfectly acceptable if the patient:

- does not routinely participate in activities which involve cutting or jumping, side-to-side sports, or heavy manual labor.

- can tolerate wearing a knee brace if he/she occasionally engages in the above.

Because an ACL-deficient knee is inherently more unstable, patients should be counseled that nonoperative treatment may increase the risk of damage to secondary stabilizers like the meniscus, and/or damage the articular cartilage, which can lead to arthritis.

In terms of surgical treatment, remember that the ACL is in the knee joint (intra-articular), and like all moving joints, the knee joint is bathed in synovial fluid. Why is this important? It’s important because synovial fluid inhibits healing. Intra-articular ligaments generally won’t heal even if the ligament is sutured together. This is why surgical treatment consists of replacing the entire ligament, known as ACL reconstruction. Surgical treatment is recommended in:

- younger, more active patients (reduces the incidence of meniscal or chondral injury)

- children (strongly consider operative as activity limitation is not realistic)

- special techniques are required so as to not damage the growth plate

- older active patients (age >40 is not a contraindication if high demand athlete)

- ACL tears with associated injuries

- PCL tears

- medial collateral ligament (MCL) or lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tears

- meniscal tears

- prior ACL reconstruction failure

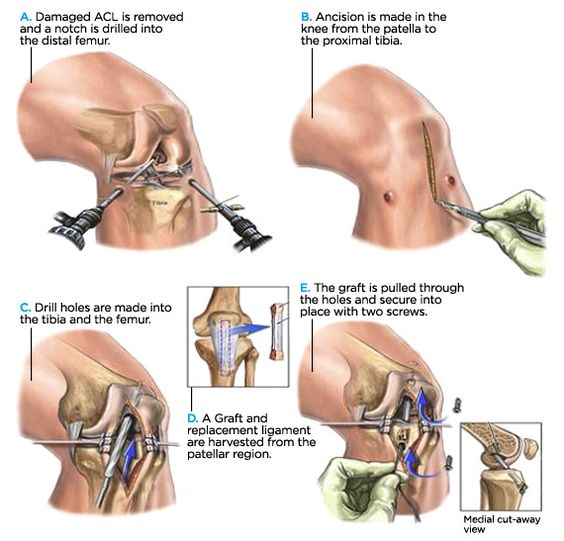

The surgical technique is arthroscopic; a fiber optic camera and various instruments are used to remove the torn ligament and clean out the damaged tissue, followed by the creation of bone tunnels and placement of a graft in the same anatomical position as the original ligament (Fig 6). Multiple technical issues exist with regards to tunnel placement, use of single vs double-bundle grafts, and secure fixation of the graft. However, regardless of technique, the key point is that the reconstruction is anatomic. Another important factor is the type of graft to use. Graft choices can be broadly classified as autograft (your own tissue), or allograft (someone else’s). Each has its pros and cons, and if you are considering ACL reconstruction, you should go over these issues very carefully with your orthopedic surgeon before undergoing the procedure.

What happens after ACL surgery?

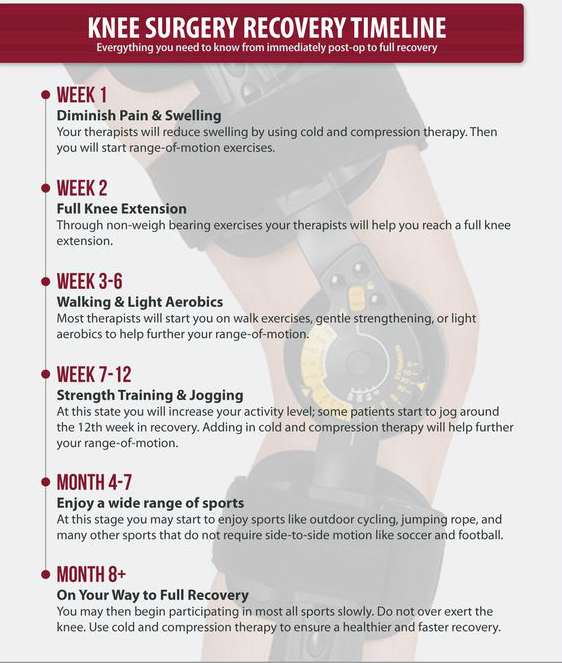

Immediate post-op protocols emphasize aggressive control of swelling, achieving full passive extension, and early weight bearing with a brace. Exercises which minimizes strain on the new ligament begin within 2-3 weeks after surgery, and progress over a 4-6 month time frame. A typical timeline is shown in Fig 7. One special note about bracing. During the postoperative rehab period, patients need to wear a special ACL brace (Fig 8). Studies have shown the graft is at its weakest 6 to 12 months after surgery (the graft gets weaker before it gets stronger). Eventually, the graft transforms or remodels into a normal ligament, however, the remodeling process can take up to a year.

Fig 7

Fig 8

Got a question about this topic? Click here

For more information about this website, click here

References

Orthopaedic Knowledge Update (OKU) 11, Published by the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2014, pp 537-538