Brian Cable MD explains osteoporosis and osteopenia.

How is osteoporosis defined?

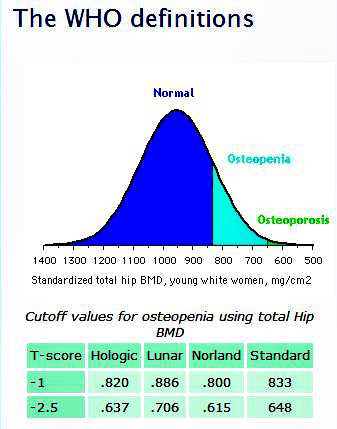

Brian Cable MD explains osteoporosis and osteopenia. We all lose bone mass as we age. Sad, but true. Past a certain point, however, this loss of bone mineral density (BMD) changes the overall architecture (thus strength) of the bone and makes the bone susceptible to fracture. The definitions of both osteoporosis and osteopenia are based on the degree of BMD loss. According to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, osteopenia is defined as having a BMD between -1 and -2.5 standard deviations from the normal mean, and osteoporosis is defined as having a BMD of -2.5 below the normal mean (Fig 1). Unfortunately, for most people, this technical definition is not that helpful. Just remember that both osteoporosis and osteopenia refer to a loss of BMD within specific ranges. Osteoporosis is worse than osteopenia in terms of how much BMD has been lost, and carries a higher risk of sustaining a fracture.

What causes osteoporosis?

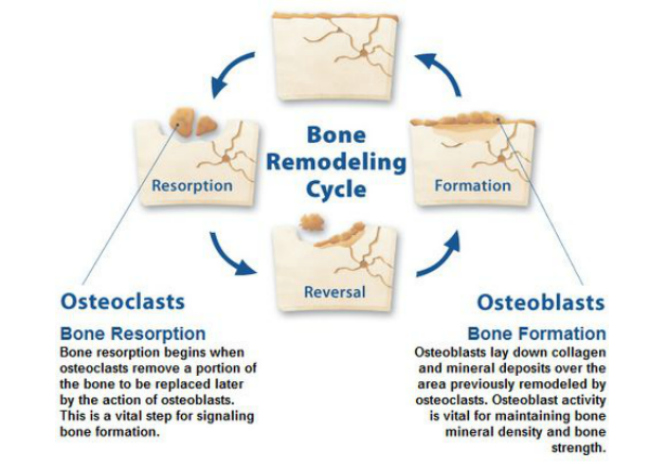

Throughout our lives, bone is continually being added to and removed from our skeleton, a process known as remodeling (Fig 2). Our bones are considered dynamic because, through this remodeling process, they can respond to any change in stress placed upon them by their environment. This response can go in either direction; for example, in response to the increased stress, impact exercise can increase bone density, whereas a zero-G environment will result in a rapid loss of BMD (a serious problem if you’re an astronaut).

In remodeling (Fig 2), different cells are responsible for adding and removing bone. When we are growing, more bone is being added than removed, resulting in a steady increase in bone mass that “peaks” in our early twenties. For the next several decades, the bone making cells (osteoblasts) are in a relatively steady state with the bone removing cells (osteoclasts), resulting in a BMD which gradually decreases over time. Of note, this decline happens in everyone, so the higher your BMD is at its peak, the longer your skeleton stays above the range for osteopenia or osteoporosis.

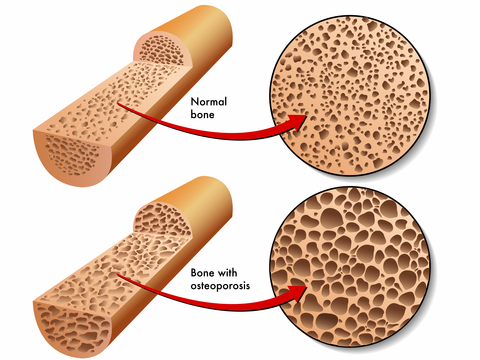

Starting at around 50 (age can vary), the osteoclasts-osteoblast balance changes; less and less bone is made than removed. The rate of decline begins to increase, particularly in postmenopausal women. This imbalance results in a quantitative, not qualitative, disorder of bone mineralization. In other words, osteoporotic bone is normal; there is just less of it (Fig 3).

What are the risk factors for osteoporosis?

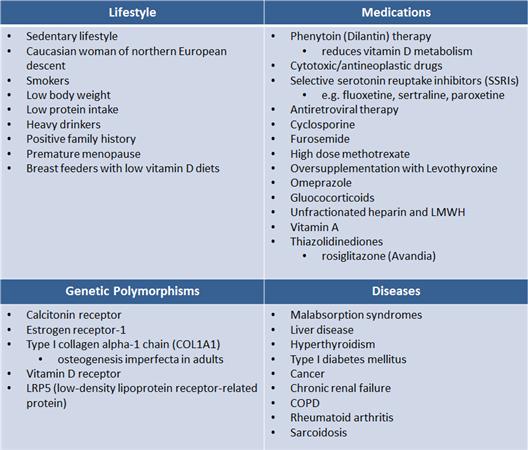

Brian Cable MD explains osteoporosis and osteopenia. Calcium intake, physical activity, early menarche, and late menopause are associated with higher BMD, whereas smoking, family history, white race, and low body weight are considered significant risk factors for the development of osteoporosis or osteopenia.

For a complete list of risk factors, see (Fig 4). All can be linked to either:

- A failure to build peak bone mass as a young adult.

- Bone loss in later life

What conditions are associated with osteoporosis?

The main consequence of weakened bones is an increased risk of fractures, with a direct relationship between the degree of bone loss and fracture incidence. Known as fragility fractures, several areas are particularly vulnerable:

- wrist fractures, which occur most commonly at age 50-60 years

- vertebral fractures (known as compression fractures), which occur most commonly at age 60-70 years

- hip and pelvic fractures, which occur most commonly at age 70-80 years

Overall, the numbers are staggering: 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures occur each year.

- 700,000 are vertebral fractures

- 300,000 are hip fractures

- 200,000 are wrist fractures

Are there different types of osteoporosis?

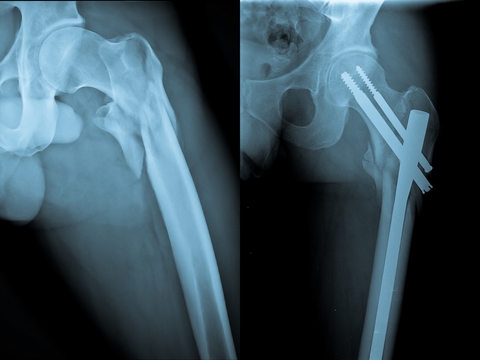

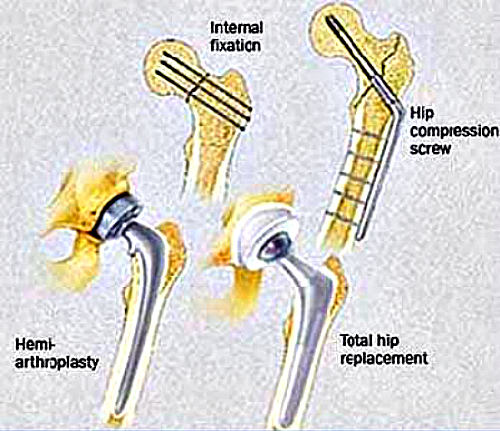

Yes, there are basically two types. Type I is known as postmenopausal (50-70), and Type II occurs later (after 70), and is known as age-related. The main important distinction is that Type II osteoporosis tends to involve fractures of the hip and pelvis. These fractures often require surgical treatment and carry a much more severe prognosis (Fig 5). There is also secondary osteoporosis, which, as the name suggests, is more directly linked to a specific condition, disease, or illness.

Who gets osteoporosis?

- female: male ratio is 4:1

- age bracket

- postmenopausal osteoporosis is highest in women aged 50-70 years

- age-related osteoporosis begins after 70 years

- secondary osteoporosis begins at any age

- men have a higher prevalence of secondary osteoporosis

What’s the prognosis for fragility fractures?

Vertebral fractures are associated with a significant decrease in the quality of life due to:

- Humpback deformity (known as kyphosis Fig 6). If severe enough, this deformity can decrease lung capacity and function, which can lead to chronic lung diseases, including pneumonia.

- Chronic back pain

- Loss of height. This, plus the loss of intervertebral disc space, is the main reason we “shrink” as we age.

- Poor balance, which can invite further falls and/or trauma.

- Associated with a 15% increase in mortality at 5 years, compared to uninjured people of the same sex and age.

Of note, a history of 1 vertebral fracture results in 5 fold increased risk of 2nd vertebral fracture and 5 fold increased risk of hip fracture.

A history of 2 vertebral fractures is the strongest indication for further compression fractures in postmenopausal women.

Hip fractures

- Usually require surgical treatment (Fig 7).

- Even stronger association with increased morbidity compared to vertebral fractures (even if surgery is successful).

- Reduced quality of life due to loss of mobility.

- Only one-third of patients with hip fractures return to their previous level of function.

- Associated with a 20% increase in 5-year mortality.

- Men have higher mortality rates following hip fractures than women.

A history of 1 hip fracture results in up to 10 fold increased risk of 2nd hip fracture

How is osteoporosis diagnosed?

Brian Cable MD explains osteoporosis and osteopenia. The presence of osteoporosis or osteopenia can be detected by testing for BMD. Currently, the gold standard and most widely used method for BMD testing is a special kind of x-ray, known as Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Done on the hips, lumbar spine, and forearm, DEXA scans are useful for osteoporosis screening, follow-up (after treatment), and overall prediction of fracture risk.

BMD testing by DEXA indicated in women at least 65 years of age and men at least 70 years of age regardless of clinical risk factors. DEXA screening is also indicated younger individuals about whom there is a concern based on their clinical profile, such a prior history of a low energy fracture, or any of the risk factors listed in Fig 4. For those individuals who have confirmed osteoporosis (T-score -2.5 or less ), DEXA scans should be repeated at 2-year intervals in all patients and at 1-year intervals in patients who have a change in treatment.

How are osteoporosis and osteopenia treated?

Because of the increased mortality and morbidity associated with fragility fractures, the treatment of osteoporosis focuses on prevention. Multiple modalities are utilized, involving lifestyle (diet, exercise), as well as pharmacology. Because osteoporosis is a multifactorial disorder, treatment involves an individualized mixture of the above measures.

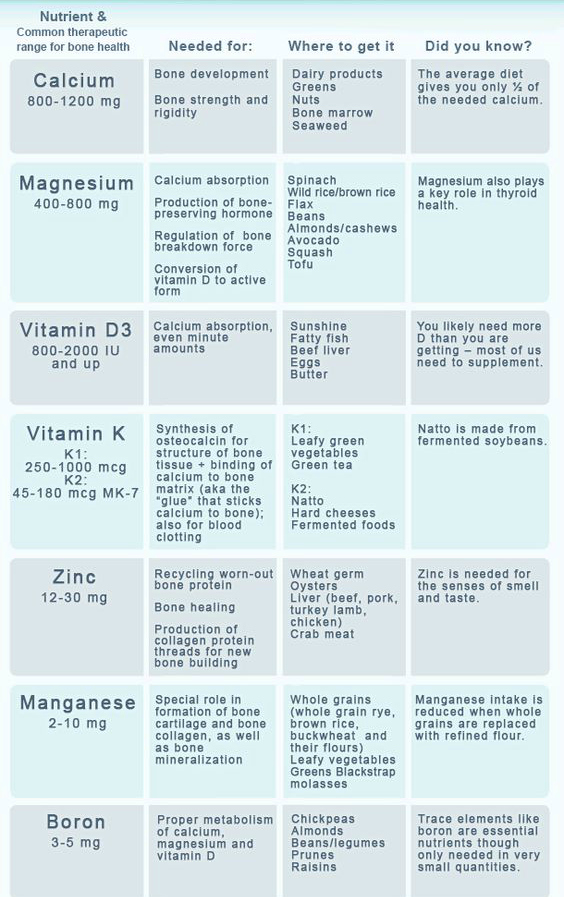

- Diet (Fig 8)

- calcium intake between 1000-1200 mg per day

- vitamin D between 600-800 IU per day

- magnesium, zinc, boron, vitamin C, and vitamin K are all important.

- Consider the calcium and vitamin D to be minimum recommended values; requirements may vary widely, depending on age, diet, UV light exposure, medicines, and underlying malabsorption.

- may be important to monitor serum levels of calcium, vitamin D, and certain hormone levels and adjust the doses if necessary.

- Exercise

- very important in building and maintaining peak bone mass.

- frequency: at least 2-3 times per week

- should include weight bearing and impact exercises

- balance and gait training exercises also very helpful to prevent falls

- walking considered ideal, meeting all the above requirements.

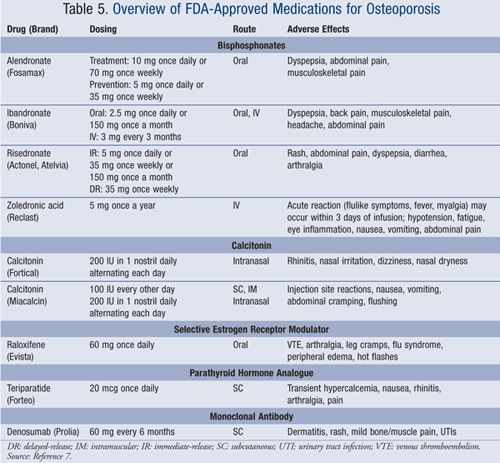

- Pharmacology

- Drugs are considered the most reliable method of treating osteoporosis.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends drug intervention in:

- Prior history of a hip or vertebral fracture

- A low BMD (T score -1.5 or less)

- High probability of sustaining a fragility fracture (particularly hip) based on known risk factors

- Medicines (Fig 9)

- Bisphosphonates

- Conjugated Estrogen-progestin hormone replacement (HRT)

- Estrogen-only replacement (ERT)

- Salmon calcitonin (Fortical or Miacalcin)

- Raloxifene (Evista)

- Teriparatide (Forteo)

- Each of these medications has different mechanisms of action, indications, and side effects. A thorough discussion of each is beyond the scope of this post; suffice it to say that it is important for the patient to be proactive, educating herself on the risks vs benefits of each should medication be recommended.

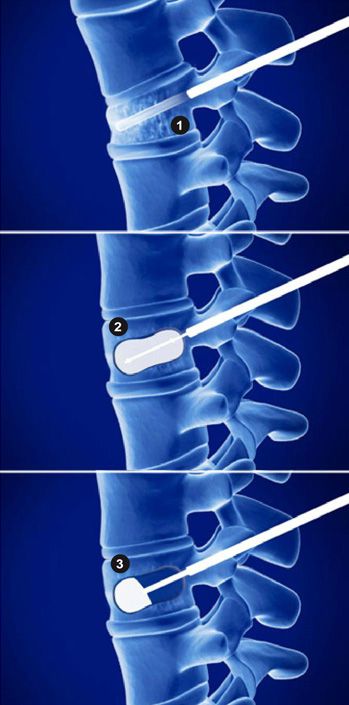

- Operative

- A quick word on operative treatment. In addition to the types of surgery on the hip as shown in Fig 5 and 7, new techniques exist to correct the lost height and angulation associated with compression fractures of the spine. This technique, known as vertebral augmentation or kyphoplasty, involves an injection of cement into the collapsed vertebra (Fig 10). Although not recommended for most compression fractures, multiple studies show a significant pain reduction compared to patients treated nonoperatively.

Got a question about this topic? Click here

For more information about this website, click here

References

Orthopaedic Knowledge Update (OKU) 11, Published by the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2014, pp 193-206